John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London turns 40 today. To this day I can’t decide if I love it, like it, hate it, or merely respect its ambition — it’s like that weirdo cousin who smells of body odor but still manages to gain your respect with his impeccable frisbee abilities.

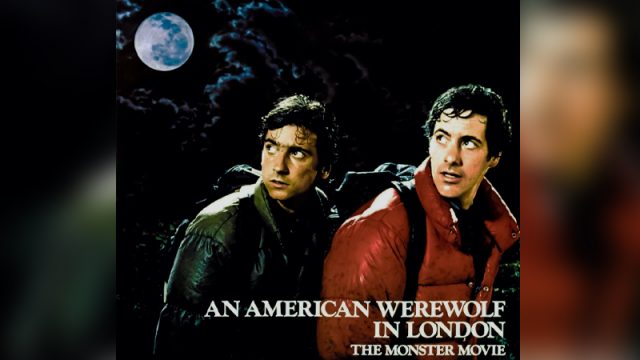

For those unaware, Werewolf follows a pair of Americans, David and his pal Jack, who are attacked by a werewolf whilst backpacking across the moors in Yorkshire. David survives the ordeal mostly unscathed, except for the fact that he too is now a werewolf, becoming the titular An American Werewolf in London.

Really, that’s it. That’s the plot. While Landis interweaves a handful of interesting characters into the framework, the bulk of the relatively short 97-minute runtime is spent building towards David’s eventual transformation. As such, we don’t really care about Jenny Agutter’s nurse Alex Price much less her spontaneous love-at-first-sight affair with David any more than we care about those weirdos at the Slaughtered Lamb. Why should we? They don’t do anything.

Take, for example, John Woodvine’s Dr. Hirsch, who spends a great deal of time learning what the audience already deduced from the title — there’s an American werewolf in London. Sure, his investigations lead to some eerie world-building, but mostly it feels like the character exists to pad the runtime.

Really, what makes Werewolf click are the peculiar elements sprinkled throughout, including that random, though brilliantly insane, Nazi werewolf dream sequence:

As well as that brilliant transformation bit:

A collection of scenes involving David’s friend Jack, who appears throughout the film as a decomposing corpse, are effectively creepy, but also darkly humorous in the way David reacts to Jack’s disgusting figure. I first saw the flick on cable TV back when I was a kid in the mid-90s and I vividly recall feeling ill whenever Griffin Dunne appeared on-screen covered in Rick Baker’s Oscar-winning gore prosthetics. It certainly didn’t help that the scene takes place over breakfast.

RELATED: Exclusive Skinwalker: The Howl of the Rougarou Documentary Trailer

Much like he did with The Blues Brothers a year earlier, Landis blends different genres — in this case, horror and comedy — to create a truly unique film experience. Everyone plays their roles straight even as the absurdity levels rise to near catastrophic levels.

At one point, David wakes up naked at a zoo after a night of murder and proceeds to run about frantically searching for clothing. He even happens upon a young boy during which this happens:

This bit only works because it actually feels perfectly in step with the plot. In other words, the story never detours just so Landis can have a few laughs. Where else would a werewolf sleep after stuffing his gut the night before?

Later, David meets up with Jack (now a skeleton) at a porn theater and ends up engaging in a witty back-and-forth with his victims, all of whom tell him (with shocking matter-of-factness) to commit suicide in order to end the nightmare.

Yeah, the porn stuff is a bit much, but it also adds to the plot’s ever-escalating absurdity. Indeed, explicit sex meshed with extreme violence raises discomfort levels by about 150%, but that’s obviously the point. More precisely, it actually plays into the film’s running theme of nature vs. nurture and fulfilling our most basic natural instincts.

Indeed, the opening conversation between David and Jack focuses on the duo’s desire to find and bed a woman during their backpacking adventure, while David-as-werewolf’s sole motivation is quenching his seemingly bottomless appetite. Simply put: as a man, David wants sex. As a wolf, David wants food. And his carnal desires as both a man and an animal lead to horrific consequences. (Note how the werewolf itself walks on all four legs — it’s more beast than man.)

David’s natural tendencies also pave the way for a moralistic tale, as guilt contributes to his increasing instability. During the opening attack, David’s natural flight-or-fight instinct prompts him to flee the scene as quickly as possible, leaving Jack to certain death. Only when his senses return does David make the (admittedly heroic) decision to turn around and help his friend, except by then it’s too late. Throughout the remainder of the film, David battles with his personal guilt in the form of visitations from the people he’s murdered; and his unwillingness to kill himself in order to spare others only increases his shame. Although, you can’t fault the kid for refusing to take the very unnatural course of suicide, particularly since the evil he currently possesses came about by no fault of his own.

Landis seems to believe our natural instincts as human beings overpower basic emotions such as love, respect, and remorse. While David certainly doesn’t deserve his eventual fate, his decision to run from responsibility ultimately paints his character in a problematic light.

Intriguingly, Landis originally wanted to cast Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi, which might have sold the comedy angle a little better. (Honestly, can you imagine that film?)

Still, despite such intricacies, An American Werewolf in London seems to revel a little too much in its own genius. As Roger Ebert explained in his review, the film “seems curiously unfinished, as if director John Landis spent all his energy on spectacular set pieces and then didn’t want to bother with things like transitions, character development, or an ending.”

Much like Blues Brothers, Werewolf is constructed as a series of short vignettes, with each topping the last until a batshit crazy finale. Landis builds towards the ultimate punchline — a final scene in which Alex foolishly attempts to confront David-as-werewolf in an alley only to be attacked by the beast before a police officer takes it down. We see human David lying dead on the concrete, his body punctured with bullet holes. Alex cries. Landis quickly cuts to credits — the cinematic equivalent of a mic drop — played over “Blue Moon” by The Marcels.

Only then do we realize we’ve been had. For all its “romance” and supposed drama, the real joke was that audiences believed love would conquer all.