Our access to sharing has never been greater. Through social media and the internet we can tell the world our thoughts, feelings, meals, how cute puppies are, or our political ideology. While we have this technology at our fingertips, we seem to be losing our ability to interact and connect with the people closest to us. 2014 saw the release of two films that deal with our fear of the people we say we love. Love is perhaps the most powerful of all human emotions because we are taught to want and desire it, but it also leaves us at our most vulnerable. In David Finchers Gone Girl and Jennifer Kents The Babadook, we see the ties that most intimately bind us brought into the cold light of day. In both films, these relationships are put under a microscope to reveal how tenuous and powerful those bonds are.

David Finchers Gone Girl, with a screenplay Gillian Flynn (based on her novel), begins with a disappearance. Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) returns home after a morning out to find his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) missing. The police are soon called, the press is alerted and the case of the missing beautiful woman whom everyone praises takes on a life of its own, as we hear two different versions of the relationship from Amy and Nick.

Before all the twists and turns, Gone Girl opens with Nicks voiceover. When I think of my wife, I always think of the back of her head, he says.I picture cracking her lovely skull, unspooling her brain, trying to get answers. The primal questions of a marriage: What are you thinking? How are you feeling? What have we done to each other? What will we do?Amy is unknowable. She is a secret, inside of an enigma inside of an onion to her husband. While Nick is revealed to be a less than stellar husband, Amy is revealed to be something cruel and malicious.

Under Gone Girls glossy, Hollywood, award-season exterior is something much darker and subversive. In a climactic scene, which would fit into any film in the New French Extremity, the films physical violence is matched by its emotional violence. From the ecstatic heights that are reached when Nick and Amy first meet, to the betrayals and blood that permeates their life upon Amys disappearance, Gone Girl paints a bleak and complicated view of the world and of marriage. Its easy enough to commit yourself to someone when love and hope are what you have; thats where the movies tend to end, but Gone Girl begins after those attributes have long left the characters. The question Gone Girl continually asks is, how far can someone push you? After the courtship and marriage have been performed, who will your partner turn into and who will you become?

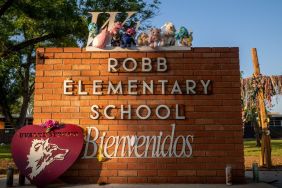

The Babadook is seemingly more concerned with the idea of the supernatural bogeyman. Jennifer Kents feature film debut follows the story of Amelia (Essie Davis), whos raising her son Samuel (Noah Wiseman) on her own after her husband is killed driving her to the hospital to give birth. Samuel is now six and exhibiting the behaviors of the dreaded problem child. One evening, Samuel takes a book off his shelf and Amelia reads the creepy and threatening story of Mister Babadook to him. Samuel then begins to see the Babadook and continually warns his mother about its advances. Amelia struggles to hold on to her sanity, while the mysterious figure of the Babadook draws closer.

The Babadook has captured the praise of audiences all over the world after its successful screening at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. While many are heralding The Babadook as one of the best contemporary horror films, its interesting to note that the film succeeds because its not afraid to get personal. The story hinges on the relationship between Amelia and her child with a handful of other characters on the periphery. The intimacy in this film is palpable and Kent works to establish how these two characters have become so distanced from their community. Like Roman Polanskis early films or Kubricks The Shining, fear and tension grows because evil, violence and anger are already present before the film even begins.

Amelia is still bereft in the grief she feels over losing her husband and must manage her growing sons dependence on her. As he begins to act out, he become a source of embarrassment because society sees the child as a direct reflection of the parent. By being Samuels sole parent, Amelia is forced to give parts of herself she simply no longer has. In fact, it is often Sam who is able to parent most effectively. He insists to his mother that hell fight the Babadook and makes them promise to protect each other. He is the one to pull Mister Babadook from the shelf and ask his mother to read it to him, which kicks off the action of the film. Sam has sensed the otherworldly presence in the house, and rather than run from it, he tries to face it. Kent imagines the Babadook as a personal terror in all of us, one which never leaves, but grows manageable as we get older. The Babadook shows us that the most powerful familial bonds are forged when those monsters, whatever shape they come in, rear their ugly heads.

Both Gone Girl and The Babadook play on the popular tropes of fear within the home. When youre left with family (whether they are by blood or chosen), you are at their mercy and they are at yours. Pain of many different kinds can be inflicted. Both of these films are fictionThe Babadook is a modern day fairy tale and Gone Girl is a heightened reality that has been condensed in a pressure cookerbut they succeed because no matter how fantastical they are, they feel too close for comfort.

Alexandra West is a freelance horror journalist who lives, works, and survives in Toronto. Her work has appeared in the Toronto Star, Rue Morgue, Post City Magazine and Offscreen Film Journal. In December 2012, West co-founded the Faculty of Horror podcast with fellow writer Andrea Subissati, which explores the analytical side of horror films and the darkest recesses of academia.