7 out of 10

Cast:

Rachel Weisz as Rachel Ashley

Sam Claflin as Philip

Iain Glen as Nick Kendall

Holliday Grainger as Louise Kendall

Andrew Knott as Joshua

Poppy Lee Friar as Mary Pascoe

Katherine Pearce as Belinda Pascoe

Tristram Davies as Wellington

Andrew Havill as Parson Pascoe

Vicki Pepperdine as Mrs. Pascoe

Bobby Scott Freeman as John

Harrie Hayes as Tess

Directed by Roger Michell

My Cousin Rachel Review:

Beware remaking a classic. That should be the first rule any filmmaker attempting a well-made, well-known film (even if it is 70 years old) should think to themselves. Their choices have entered the popular conscience, when the unconventional ones, to the extent that changes even if objectively right can seem the wrong step. This leaves the filmmaker stuck either copying or disrespecting the original. But the trap is even greater than that. Even if the previous versions are so old modern audiences are not familiar with them, the urge to strike out on one’s own and create a separate identity for the new film often means differentiating from the older version even when it made the choices it made for clear reasons. Beware remaking a classic, even an old one.

Wealthy landowner Philip (Claflin) has heard much about his ‘cousin’ Rachel (Weisz) but never met her. The wife of his own cousin Ambrose, the man who raised him, Rachel has always been an enigmatic figure in letters but never a person. At least until Ambrose dies and Rachel, with nowhere else to go after Philip inherits everything, arrives in England to live. Before he knows it, Philip goes from suspecting Rachel to coveting her, desiring to give her all he has but only on the condition that she reciprocate the same. Ignoring all the pleadings of his family and friends, Philip continues his pursuit but with fewer and fewer results. When he suddenly turns sick himself, the memory of Ambrose’s letters returns, along with their warning not to trust Rachel.

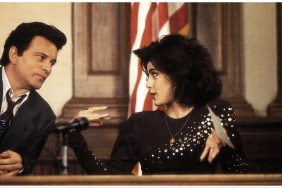

My Cousin Rachel has always had one overarching problem; it is about Rachel, but because it is a mystery told from Philip’s point of view, she is always kept at a distance – unknown and unknowable. It was a problem in the bestseller by Daphne du Maurier (Rebecca) and in the original film with Olivia de Havilland and a young Richard Burton. Partly that’s for the purposes of suspense and partly to play up the question of who the true antagonist is – Philip or Rachel. It’s also the point with the most opportunity for differentiation from previous versions and yet Michell never solves this problem despite attempting to aim directly for it.

Michell’s primary focus is on Rachel and how it is for her to live in the world she does. She knows what leverage she does and doesn’t have and is not afraid to use all of it, not out of spite or cruelty but out of necessity. She is smart enough to know how unfair it is but perhaps kind enough not to allow that knowledge to turn her bitter. Within that ‘perhaps’ are held oceans, however, as every time Michell get close enough to Rachel to be definitive on what she thinks, he must pull away to keep the mystery intact. Weisz is magnetic as Rachel, but then she’d have to be. The entire point of Rachel is that she draws people to her to the point where, even when they suspect her of dark deeds, they still want to be the center of her attention. And she must do so while conveying both worldliness and a certain amount of innocence, to keep the whiff that the worst suspicions about her motives form settling on her.

It’s a good instinct on everyone’s part, but beyond the textual limitations on Rachel it’s further hampered by Michell’s other major choice. Taking advantage of several years of advances in what society will allow, Michell runs straight at the sexual longing between Philip and Rachel and Rachel’s cognizance of her role in society. Which is to say he skips any circumspection and, in a period known for extremely formal relations between individuals, attempts to be as blunt as possible while admitting to nothing. While the older versions have been more innuendo laden due to rules outside of the text that played to the strength of the story, increasing the question of what Rachel’s motives might be. A willingness to put everything in the open further emphasizes the strangeness of not doing so with Rachel.

Nor does Claflin quite have the chops to carry off Philip’s many changes of heart. As time has passed, the fury of Philip’s desire, eventually flowering into a physical assault on Rachel when she won’t do what he wants, has become more and more questionable. Not because he is supposed to be pure as the driven snow – every version of the story has wanted to put at least some suspicion on Philip that he is secretly the villain and doesn’t realize it – but because Michell can’t ever get away from him. No matter what line Philip crosses, Michell is stuck following the story through his eyes (unless he chooses to make whole sale changes, which no one seems to want to do) and at best being ambiguous even about the worse actions. If Claflin were more charismatic, they might be able to carry the dynamic off anyway – it worked for Burton – but he’s far better at pulling off Philip’s sunnier side than his rabid need.

All of which sounds more damning than it is. Michell has made a beautiful film, aping some of the low illumination look of Barry Lyndon, and Weisz truly shines in the title role. But it’s trying to do two diametrically opposed things – recreate Rachel as a feminist icon and keep her status a suspicious potential murderer – which keep it spinning its wheels and unable to gain any real traction.

My Cousin Rachel

-

My Cousin Rachel

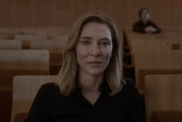

Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Holliday Grainger as "Louise" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Iain Glen as "Kendall" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" and Director Roger Michell in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Iain Glen as "Kendall" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

-

My Cousin Rachel

Rachel Weisz and Sam Claflin in MY COUNSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. Copyright Fox Searchlight Pitures 2017

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Iain Glen as "Kendall" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip", Iain Glenn as "Kendall", and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Rachel Weisz as "Rachel Ashley" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

Sam Claflin as "Philip" and Iain Glen as "Kendall" in MY COUSIN RACHEL. Photo by Nicola Dove. © 2016 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

-

My Cousin Rachel

-

My Cousin Rachel