Hey there, fellow soundtrack lovers! As Ned Ryerson would say, we’ve got a doozy today! First, we’re going to take a look at La La Land Records’ Harry Potter: The John Williams Soundtrack Collection along with the label’s Days of Thunder expanded edition by Hans Zimmer. Then, we were given the incredible opportunity to interview Émoi’, composer of the upcoming Nicholas Cage thriller Willy’s Wonderland, who took the time to discuss everything from his scoring process to his fear of Chuck E. Cheese. And finally, we’ve got a terrific interview with renowned composer Henry Jackman, who was kind enough to discuss his work on Joe and Anthony Russo’s upcoming drama Cherry.

Let’s do this thing!

NEWS

First, in case you missed it, check out the first track to Tom Holkenborg’s score for Zack Snyder’s Justice League. The track, titled “The Crew at Warpower,” runs nearly seven minutes and kicks all kinds of ass! I can’t wait for this score!

The #SnyderCut score wouldn’t have happened without all of you demanding it.

Here is your first taste.

Enjoy. https://t.co/YEtFHRvli4

— Tom Holkenborg (@Junkie_XL) February 17, 2021

Danny Elfman has signed on to compose the score for Sam Raimi’s Doctor Strange sequel! This is awesome news as the pair have teamed up on a number of high profile projects, including Darkman, the Spider-Man trilogy and Oz: The Great and Powerful, among other collaborations. Good move, Marvel!

Spider-Man Composer Danny Elfman to Score Raimi’s Doctor Strange 2https://t.co/I63gBnBrMx

— ComingSoon.net by Mandatory (@comingsoonnet) February 18, 2021

I’m thrilled to share #WW84: Sketches from the Soundtrack, which features the original experiments, musings and sketches that then became the final soundtrack for @WonderWomanFilm. Check it out at https://t.co/hFFpVmzD9X! pic.twitter.com/6UIX7gnjA4

— Hans Zimmer (@HansZimmer) February 5, 2021

REVIEWS

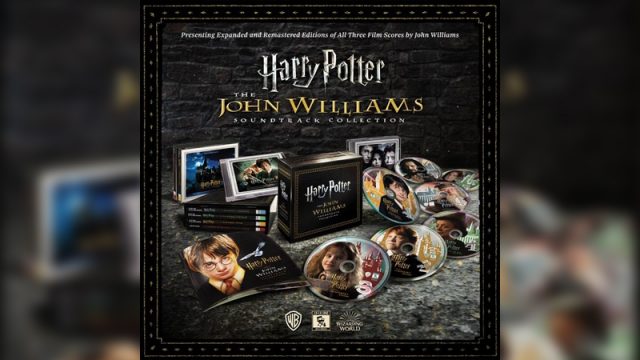

Harry Potter: The John Williams Soundtrack Collection

John Williams

Christmas came early this year! Like, waaaay early. It’s only February. And yet, La La Land Records surprised the film score community when it announced the limited reissue of Harry Potter: The John Williams Soundtrack Collection, a massive 7CD set comprised of expanded scores for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and (best of all) Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Each film score comes with its own production booklet, while the box set entire features a 44-page booklet featuring general music information and track listings fro all three scores.

Produced, assembled and mastered by Mike Matessino, all three scores were fully remastered from the original 5.1 and stereo mixes by Simon Rhodes (SORCERER’S STONE & CHAMBER OF SECRETS) and Shawn Murphy (PRISONER OF AZKABAN). For SORCERER’S STONE, the original analog master tapes were newly transferred at high resolution and the score was meticulously re-edited and output from the first-generation material for maximum quality.

The exclusive, in-depth liner notes are written by Mike Matessino and the release’s wizard-worthy art design is by Jim Titus.

I’m not going to jump into a detailed review of each score as Williams’ work has been covered any number of times since premiering way back in 2001. Suffice to say, I appreciate Sorcerer’s Stone, really like Chamber of Secrets and absolutely adore Prisoner of Azkaban. Of the three, Azkaban supplies the most unique sound and is a fine example of blockbuster film scoring, even if it fails to carry over themes established in the previous two entries. Azkaban is dark, scary and a whole lotta fun and packed with soaring themes such as “Buckbeak’s Flight” and haunting cues such as those found in “Rainy Nights, Dementors and Birds,” all of which perfectly capture Alfonso Cuaron’s drastically different approach to the popular franchise. And while the music lacks that, ah, magical innocence heard in Sorcerer’s Stone and the swashbuckling Chamber of Secrets, it still packs an emotional punch; and escalates to near operatic levels thanks to Williams’ terrific use of choir and clever use of period instruments.

That’s not to diminish Sorcerer’s Stone or Chamber of Secrets. For the former, Williams produced as thrilling an adventure score as one could hope. The only gripe is that nothing in Sorcerer’s Stone, outside of the main theme, tickles the imagination. We’ve heard this Williams countless times before in his scores for Hook, Home Alone and Star Wars. Yes, it’s Sorcerer’s Stone is an excellent score; and yes, there are moments that will quite literally take your breath away, but at a whopping two hours and fourteen minutes, you may long for a little more, ah, variety to go with the familiar lighthearted adventure beats the maestro has employed so often throughout his astonishing career.

Chamber of Secrets is the better of the two early films and gave Williams an opportunity to go a shade darker this time ’round. Notably, the main theme for the titular Chamber of Secrets is thrilling to behold. While Fawkes’ theme ranks among the series’ best, particularly when it’s given the chance to really explode during the film’s climax.

Notably, another downside to the first two entries are the abundance of themes that are introduced … only to be dropped in later entries. Williams scored the first three films before passing the baton to Patrick Doyle, who then ceded duties to Nicholas Hooper. By the time Alexandre Desplat took the reins for the last two films of the blockbuster franchise, nearly all of Williams’ themes had been discarded in favor a more modern, disconnected sound. As such, themes heard in Sorcerer’s Stone, such as the one used to signal Voldemort, are little more than cruel teases of what could have been had the maestro hung around for all eight films.

For more information on Harry Potter: The John Williams Box Set, visit La La Land Records.

Click here to purchase the original soundtracks!

Days of Thunder

Hans Zimmer

Oh, Days of Thunder, where have you been all my life? As a fan of late 80s/early 90s cinema, I had inexplicably stuck my nose up at Tony Scott’s race car drama and discarded it as little more than a Top Gun knockoff. Then, sometime last week, I stumbled upon the score and instantly fell in love with Hans Zimmer’s chill-bump-inducing sound. Sure, it’s cheesy and more in line with, say, Broken Arrow than Crimson Tide, but Days of Thunder’s soundtrack is a blast from start to finish. And, honestly, at $19.99, the expanded score found at La La Land Records is actually quite the bargain. This is a roll-the-windows-down-and-drive-real-fast-during-a-summer-evening type of soundtrack if you catch my drift, replete with electronic beats, killer drums and Zimmer’s patented synths and keyboards.

And, hey! The film actually isn’t too bad, either …

For more information of Days of Thunder 30th Anniversary Limited Edition, visit La La Land Records.

Interview with Willy’s Wonderland Composer Émoi’

Willy’s Wonderland synopsis: When his car breaks down, a quiet loner agrees to clean an abandoned family fun center in exchange for repairs. He soon finds himself waging war against possessed animatronic mascots while trapped inside Willy’s Wonderland.

Émoi composed the score, wrote and sang all the lyrics to the songs in the film and also provides the voice of the evil animatronic Willy. He was gracious enough to speak with ComingSoon.net about this wild new adventure.

Check out the soundtrack for Willy’s Wonderland here!

ComingSoon.net: What drew you to Willy’s Wonderland?

Émoi: I grew up on these kinds of films, and I absolutely love this genre. If I were given the choice to score any film ever made, I would choose Willy’s Wonderland…and that is me being completely honest. The fact I got the job, makes me feel so fortunate and grateful.

CS: The movie seems to prey upon our fears of those freaky Chuck E Cheese robots we all grew up with — and it sounds like you had a couple of particularly creepy incidents with said robots as a kid. How did the Chuck E Cheese brand, and your memory of it, inspire your score?

Émoi: Chuck E. Cheese was a really big thing when I was growing up. The place had its own very unique vibe. I made so many memories there with all my friends, playing skee-ball, eating our body weight in pizza, trading our tickets for prizes. It was magical, and yet, there was this unspoken discomfort caused by the oversized animatronic characters that for the most part hunched life-less on the stage, and then would suddenly spring to life and start singing. So for Willy’s, the music had to be all those things: magical, fun, entertaining, quirky, nostalgic, and frightening.

CS: You wear a lot of different hats in the film — which aspect was the most fun? The most difficult?

Émoi: Voicing Willy was pretty darn fun. I mean, I had a blast writing the score, but scoring and recording are a heck of a lot of work. Voicing Willy and singing the songs wasn’t stressful at all, it was actually a really nice escape. The hardest part for me was the role of Music Editor. Because I didn’t much enjoy chopping up my own score (laughs). It’s so hard because as composer, you fall in love with an idea, and as Music Editor you have to objectively cut the music to the updated edits, and sometimes you have to cut or modify that idea the composer was in love with. There were a few times I had some real arguments with myself (laughs).

CS: So, this is your first feature film correct? How challenging was the production overall compared to some of the other work you’ve produced — and considering this is your first full length feature?

Émoi: Yes, this is my first full length feature. And almost every project I’ve done prior to Willy’s was a 2-3 month commitment at the max. Willy’s was over a year, and 8 months of it was a solid 24/7 work schedule. I barely slept at all. The good news is, it kept me very socially distanced, and my experience of the year 2020 would have been pretty much exactly the same whether or not there was a pandemic. I didn’t miss out on anything I wouldn’t have missed out on anyway.

CS: From what I’ve read, you had to get really creative with this one due to the pandemic. What were some of the tricks you utilized to create this score?

Émoi: The pandemic limited our ability to collaborate in-person. Which meant no studio musicians or singers could come into my studio. I couldn’t have a music editor, assistant, engineer, or anyone working next to me. So there weren’t really any tricks – I wish there were – but it just meant I had to work 10 times harder, and sleep a heck of a lot less.

CS: What is your scoring process like?

Émoi: The way I typically write, is I’ll read a script, or listen to a director talking about his vision, and I’ll start hearing the music in my head. Then I’ll record myself singing the various parts I’m hearing. I’ll then listen to the recording and try to piece it together on piano. Then I’ll take the piano version, and start imagining what instruments should be playing the notes. Less typically, but often, I’ll also sit at the piano and have the picture play as I fumble around on the keys until I hit the notes that connect with what I’m seeing and feeling, then I’ll start build it out that way.

CS: This film looks absolutely batshit crazy—how much fun is a project like this? And how much freedom overall does it provide a composer?

Émoi: Batshit crazy is an understatement (laughs). This movie is a shit house rat dropping acid at a 3 a.m. rave hosted by a bag of cats. And that’s a big part of why it is so amazing. I cannot express in words how fun it was to work on this film. I had the greatest team behind me, and they supported my vision so much. That, and the fact that the pandemic prevented in-person discussion, I was given probably more freedom than what is typical.

CS: What was your collaboration like with the director?

Émoi: It was incredible. Kevin and I had an initial call in October of 2019, and we hit it off like we’d been friends for years. We had the same taste in films, music, pretty much everything, so working together was extremely fun.

CS: What aspect of the score are you most excited for people to hear?

Émoi: The character sing-alongs are going to no-doubt be what is talked about as they are catchy and ridiculous. But I’m hoping viewers really tune-in to some of the darkly beautiful and nostalgic aspects of the score as well.

CS: Do you have any upcoming projects you’d like to share?

Émoi: I am very excited about a pilot that I am finishing up that is a supernatural detective thriller. Besides that, there are also a few feature length scripts I’m reading, as well as a potential TV series. With the pandemic still looming, things are slowed down a bit, but I think the future is bright!!

Interview with Cherry Composer Henry Jackman

Henry Jackman is one of most accomplished composers working in the industry today having scored films such as Kick-Ass, Kingsman: The Secret Service, Captain America: Civil War, Kong: Skull Island, The Predator and many others. His latest project, the upcoming film Cherry, releases in theaters on February 26 and globally on Apple TV+ on March 12. Jackman was kind enough to sit down with ComingSoon.net to talk about the anticipated film from Joe and Anthony Russo.

ComingSoon.net: What drew you to the film Cherry?

Henry Jackman: Well, I’m very lucky in that I’ve done let’s see, two, you know, Captain America: Winter Solider and Captain America: Civil War with Joe and Anthony Russo. And they also produced Mosul and 21 Bridges. So over the years, I formed a really close relationship with them, and I was very lucky in that their next project after the hugely successful Avengers films was this very curious, really experimental and interesting artistic film, which they asked me to do the music for.

CS: Can you talk about some of the different techniques and instruments you implemented for the music of Cherry?

Jackman: Yeah, for sure. When I saw the first cut of the movie, I mean, I already knew from reading the script and from the discussions with Joe and Anthony that this was going to be a million miles away from the super hero movies that we’d done together. It was such an unusual film that I didn’t want to start just writing the specific cues straight away just to the picture. So I began to write these kind of standalone pieces based on the discussions and the script and by freezing still images and a whole range of different things, really. So there’s big speeches, it had to be really eclectic, but somehow unified, which is kind of a tall order. So although I had a theme, I mean, if I had different kind of textures, there’s a fair amount of original analog synth in there. When I say that, I don’t mean plug-ins, I mean I was actually fooling around with late 70s synths and recording them in a really old sort of way and dealing with the fact that every time you turn them on, they’re slightly out of tune and inconsistent.

There’s piano, there’s cello. And I was experimenting with ukulele and ambient harp, a zither, some strange instrument, which I didn’t quite know what it is or what it’s called. I call it the magic circle. It’s some sort of strange mallet-based instrument and it made a very nice sound. And really, I just grabbed anything from my trusty SH5 and MKS50 analog synth to a whole eclectic range of instruments. And you know, there were a couple of cues that had the strings. Oh, not to mention, I recorded the Tallis Scholars Choir, and then they’re going – and not only that, having recorded things, it was an awful lot of messing around with production technique, so I was laying things onto cassette tape and then bringing them back into the sequencer, deliberately trying to make the tone a bit more unstable because I was using a cassette machine that didn’t quite function properly.

CS: Do you find a project like this liberating at all since you’re free to do what you want to do? Or, do you find it more challenging?

Jackman: That’s a really good question. I think there is something liberating and fantastic about having no idea what something’s going to sound like because you’re not only the them and the melody, you’re creating all of the textures. It is very exciting and it’s liberating and it’s experimental. You know, it’s also a little more unknown because you don’t necessarily know if these experimental musical explorations that you’re engaged in are actually going to go anywhere, whereas if you’re writing a piece with the Symphony Orchestra, you know, the piece still has to be good but you’re not asking too many questions about the validity of the Symphony Orchestra. It’s an established format. So, I enjoy both. I really enjoyed in the case of Cherry, having such a sort of renegade approach to how to put things together. But that’s not to say that when I return to the Symphony Orchestra, there’s also many things to enjoy about using the Symphony Orchestra. I mean, thankfully I’ve got a career where hopefully I’ll get to do a bit of both. But yeah, there’s no denying. You need a bit more time when you’re creating so much new tonality. But both have their advantages and disadvantages. But as far as Cherry is concerned, I was like a sort of mad doctor in a laboratory experimenting with all these things and I definitely loved it.

CS: You’re basically underscoring a man’s descent into his own personal hell. How taxing is it on you, because I imagine you have to put in a lot of emotion to the score in order to convey the proper amount of emotion on screen to underscore the action of the characters?

Jackman: Oh yeah, no, that’s another really good question, yeah. The funny thing is, you notice that by the way, what you’re saying is in fact completely true. But you don’t necessarily notice until it’s over because you have to descend stair by stair down the staircase into the committing to the emotion and the PTSD and the madness and the experience. And because as you’re writing the score, you don’t achieve the music which supports that on day one. It’s a process. But you’re sort of slowly sinking into the absolute, you know, aesthetics of the film, kind of without realizing. It’s more like when you finally finish and you sign up on it and everything’s working and you’ve mixed everything and everything’s in the movie, you then suddenly realize, wow, that was exhausting, sort of retroactively, you know? A bit like if you hadn’t known that I’d put weights in your shoes, it’s only when you wear a different pair of shoes you go, oh, I didn’t realize I was walking around with weights — and I don’t want to sound negative. It’s a bad analogy to say it’s like walking around with weights in your shoes.

But to the extent of the commitment to the project and some of the subject matter it explores, you know, mental illness, PTSD, drug addiction. But there’s a wry humor to the movie. It dances between the serious subject matter, and it does have a layer of dark humor to it. So it’s still entertaining to watch the film, despite the fact that it has a heavy subject matter. So that’s what I bear in mind. But you’re right, I did notice when I finished, I sort of realized retrospectively just how I put everything I got into it. But you’re not so aware of that while you’re in the heat of battle. When you’ve finished, you realize you’ve left everything you had in the movie.

CS: One of my favorite cues from the whole film comes right at the end — a beautiful piece of music that feels like an exhale after this really intense experience.

Jackman: Well, exactly, yeah. Now the funny thing is, there’s a theme that comes in maybe halfway through that very long scene. I think it’s like eight or nine piece at the end. And funnily enough, that theme has been teasing throughout the movie. In fact, that tune appears in the very first piece of music in the movie. And it appears in various octave forms and different orchestrations and mangled forms. And it’s been hinted at a few times during the film. And then that last coda at the end of the film was a really great opportunity, also because of the time, you get to write an eight or nine-minute piece, it was a chance to take the theme that has been hinted at and suggested and let it really blossom into something. So I was really grateful – the way the filmmaking worked at the end left a lot of space for the music to be able to do that.

CS: And then also that opera piece that plays during a pivotal moment of the story.

Jackman: Well, that was, I think Joe was very keen on that. I think it’s a really good idea, that something – it’s also in the tradition of filmmaking. I’m trying to think, there’s only classic opera moments in [Martin] Scorsese [films], maybe there are, maybe there aren’t. I can’t recall them exactly. But it also, it’s so different to some of the experimental aspects of the score that the few pieces of Verdi really perform a great function in the overall experience of the movie.

CS: How do you think you’ve evolved as a composer over the course of your career? And would you have approached a film like Cherry the same way back in the early 2000s, when you first started?

Jackman: Oh I have no idea, is the truth. But I think, well, I hope I’ve gotten better. You never know. I can only allow other people to decide that. I mean, I was very green then. The way I approach film music is I just do the absolute best job I can, so I’m sure I would’ve held myself into it to the best of my ability had it been a lot earlier. But no doubt, I probably would have missed the mark a bit more, maybe needed a lot more help from Joe and Anthony, who by the way, are very collaborative and helpful anyway. But, yeah, it probably would have been a little early. I think once you’ve done a number of scores, even if they’re wildly different to Cherry – once you’ve done a number of scores, I think it was the right time. I think I was ready to take on the magnitude of the creative task of writing the music for Cherry, where had it been 10 years previous, I might have missed the mark.