Lee Gambins Secretly Scary column continues to look at non-horror films that are secretly horror films!

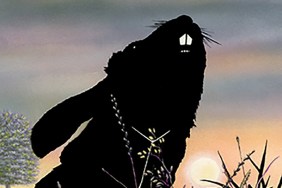

All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a thousand enemies

Adapted from Richard Adamss sweeping allegorical tale of survival and the promise of life outside despair, Martin Rosens animated film of WATERSHIP DOWN is relentlessly serious in tone, boldly grim, textually sombre, intellectually driven and deeply concerned with fear and alienation. Telling the story of a group of English countryside rabbits who leave their warren in hope for a better life, the piece sets up its principals as clearly designed and conceived extensions of a grounded concept of endurance. The film is most certainly a horror film in that it expresses mortal dangers throughout the sturdy landscape of its story and even plays with the imitable body-count narrative trope used as the skeleton of slasher movies which would become increasingly popular not too long after this rabbit odyssey would hit the screen and frighten children (and adults alike) out of their wits.

As the nature of the piece startles an audience into understanding that nothing is going to be pleasant or even remotely safe, we get an inside peek into the lives of worried rabbits who leave home after Fiver (the psychic lepus) has a vision of blood stained fields, death and decay. The central rabbits are then steadily forced into a constant and consistent state of fret, edginess, jitteriness and desperate distress. Throughout the film, the stylistic intent is also keenly disturbing and compliments the harrowing ordeals facing Fiver and his friends – the colours are earthy, restrained, moody and remarkably nightmarish in their tone which makes for a provocative and very cerebral animated outing. The film is terrifying and traumatizing whilst also thoroughly political, thematically complex and dedicated to character.

The political aspects of WATERSHIP DOWN are embedded within the text and not at all subtle, this is very much on par with George Orwells much lauded critique on communism in his seminal ANIMAL FARM, however, politics aside, WATERSHIP DOWN is stronger when you look at the thematic notions of endurance, suffrage, sacrifice, friendship and determination. However, the horrifying reality of this masterwork is that violence is a constant concern and is unavoidable. As life affirming as the film can be to some audiences, it is the pictures acute sense of drifting into the ghostly and eerie that makes it a much more rich, calculated and endearing film. In many aspects, it is the sadness of WATERSHIP DOWN that keeps it alive and keeps it breathing. The blood stained rabbits, the vicious war between the freedom fighters and the tyrannical order, the quest for happiness and refuge and the brutality of the mantra that warms all the world is your enemy makes up for a dizzying, nightmarish event, but mapped out in holistic and inclusive sensibilities. There is an understanding of grim serenity in this film, and it is that kind of sadness that nurses the morose that fuels the horrific trauma that props up WATERSHIP DOWN.

Art Garfunkel and Mike Batts song Bright Eyes not only comments on loss, despair and eternal struggle, but it also makes a bold statement that these things are inevitable. With haunting lyrics such as How can a light that burns so brightly, suddenly burn so pale? accompanying a young buck following the Black Rabbit of Death in an almost psychedelic showstopper, the song channels inconsolable heartbreak and the torment of life which systematically always leads to death. The inherent misery in WATERSHIP DOWN is reactionary to the cinematic and thematic horror, and despite the slight and muted attempts at comic relief in the form of a seagull voiced by Zero Mostel, the films mood and temperament is summarized by an early line muttered by the nervous seer runt Fiver who senses overwhelming threat: Something oppressive, like thunder.

The film delivers some harrowing sequences all born straight out of introspective horror, pontificated horror, visceral horror and politically aware horror. When a doe named Hyzenthlay pleads with the tyrannical chief rabbit General Woundwort to expand on the colonies because she and fellow does have no room to produce litters, it is a remarkably acute commentary on the state of recession-plagued London at the time, where working class families were forced to live piled next to one another and in squalor during the so-called Winter of Discontent which had the final days of Prime Minister James Callagahan turning a blind eye to the economic crisis that troubled the UK.

Theyll never rest until theyve spoiled the earth says one of the rabbits referring to human kind, and the concern with environmentalism is hinted at. This devastating destruction of the warrens and the inconsiderate and repugnant mistreatment of the land at the hand of man is a powerful ingredient but never dwelt upon, which makes the film far more intelligent than what it could have been had it been made in later years. It is not a black and white animal vs. man parable, instead it is a deeply spiritual and yet at the same time blatantly earthy account of the nasty factors of a troubled and gruesome realism. This secret horror film breathes with heaving lungs that thrive on a firmly rooted subconscious fear of forced change and drags its nervous audience to confront questions of the afterlife, nature and the natural order, an alternative creation story which involves a poignant lapine mythology and language, unapologetic violence and gender politics (which would eventually become controversial in critical circles). The film rides the perfect balance between terror and moody torment, and it is a quiet energy that moves the piece from trouble to despair to discomfort and to trauma. However, not all of the film is dense doom and gloom. The rousing moment when the rabbits reach the top of the hill and look over the rich, green meadowlands is a moment of isolated beauty and chill-inducing magic, and it is augmented in blissful beams of rare hope when Fiver cries out You can see the whole world! However this tender moment is disturbed when the all-male community realize there are no does in their new promised land, which sets them out to find some. The original doe in this male-dominated community of travelling rabbits is killed early on. Violets death is brutal and fast. She goes out to eat some blossom and is swept up by a hungry opportunistic hawk.

Amongst the rabbit brotherhood is Bigwig. This brave bunny remains headstrong for the rest of his group. The scene when he gets caught in a snare, bleeding profusely and desperately resisting death, is as harrowing and as daunting as a torture sequence in any horror film. The frenzied rescue to have his throat freed from the snare while flies buzz around his bleeding mouth is grotesque and also completely depressing leading Bigwigs comrades to pray My heart has joined the thousand, all our friends stopped running today But Bigwig rejects death, he sets himself free and shakes off the threat of mortal coil. Countering Bigwigs masculine drive is Cowslip, a fey, lascivious sissy throwback who has his own warren and access to fresh vegetables tossed aside by neighboring humans. With his limp paws and his foppish mannerisms, Cowslip is also quite the poetry buff. His warren is described as unnatural by one of our central heroes and when he quotes a poem reciting Take me on your dark journey it terrifies Fiver which jets the panicky rabbit into a stressed out state. Fivers premonitions send him into nervous insanity, and his rambling and frenzied muttering makes him a complicated, messed up character who mirrors many neurotic victimized protagonists found in many pscyh-horror films. The divide between determination and being a slave to anguish beats strong in WATERSHIP DOWN, and much like running through a field with not a care in the world, but then suddenly stopping because there are concerns that interrupt your clarity, the film reveals the wound and rips off the mask of bravery, depicting life as fleeting and fragile while embracing the darkness of realism.

When there is talk of the promised land, the film throws us into a space of bewilderment and awe – it also promises us something pleasant and beautiful, outside of the terror, dismay and morose blanket of sorrow. Like a child who refuses to understand the passing of a loved one, WATERSHIP DOWN leaves you with that painful longing which is understood by those with a damaged heart tortured and tormented by overwhelming loss.