Nearly every film owes something to a film that came before it. Often filmmakers will at least tip their hat to movies in a similar vein, signalling to the audience that they are aware of what theyre paying homage to. Its a bold move, however, to frame an entire film within a style of filmmaking that came before it. Kicking off with Ti Wests The House of the Devil in 2009 which proved that an entire film could be shot to look like a film from another decade while still creating a fresh and vital horror film for the new millennium, this trend has continued across other films which eschew the populist grainy found footage aesthetics or stylistic remnants of torture porn.

While a full throwback style film has not been attempted since, its easy to see the success of The House of the Devils influence on films such as Franck Khalfouns Maniac (2012) remake, Almost Human (2013), The Guest (2014) and It Follows (2014), which all owe a debt to the look, feel and storytelling style of the late ’70s and early ’80s. The popularity of this style can be traced back to the re-emergence of collecting VHS through hipster culture or horror fans waning interest in the more mainstream offerings of horror, which by 2009 still consisted of the Saw franchise and the emergence of Paranormal Activity. Horror fans in their late 20s and early 30s, who had loved the genre since their childhood, wanted a return to the visceral, shocking fear that led them to becoming horror fans in the first place.

Many cultural critics and theorists have situated our disposition for nostalgia as a fear of the present, where the mind retreats to a past situation which offers comfort and confirms our belief systems rather than deal with an uncertain present. This new trend in horror to either explicitly set a film in the ’80s or borrow specific elements (particularly from John Carpenters oeuvre) feeds that desire for nostalgia. But these films subvert our expectations of the genre by creating a film thats familiar in its visual presentation alongside a revision of a familiar narrative, creating films that both embrace our love of nostalgia and present something frighteningly new and unexpected.

The House of the Devil (2009)

Ti West had a modicum of success when he set out to make The House of the Devil. His first feature, The Roost (2005), generated some positive notices, but his next big effort Cabin Fever 2: Spring Fever (2009) was all but taken away from the director causing West to essentially deny having any creative hand in the film. That same year, The House of the Devil was released. Shot on 16mm film, The House of the Devil was designed to emulate the Satanic Panic films of the late 1970s and early 1980s. An opening title card indicates as much citing the impact and popular belief in Satan as real and prevalent. West used shooting styles popular in the ’70s and ’80s, including the aforementioned film stock as well as low-angle wide shots and zoom-ins to create the world of the film. While West mimicked the style of films that had come before, to the point where an unsuspecting viewing might actually mistake the film for a legitimate piece of horror from that era, what would shock viewers is the minimal but seamless integration of practical effects with progressive and modern characters. When Samantha (Jocelin Donahue) accepts a babysitting job, the film situates her in a predictable horror scenario – a beautiful young woman in a creepy house where nothing is as it appears. But West gives Samantha agency. She is capable, likeable and modern up until the very end. The infusion of a relatable character in a film framed by its nostalgia felt vital and fresh, creating an instant buzz around the film and cementing its place as one of the best contemporary horror films.

Maniac (2012)

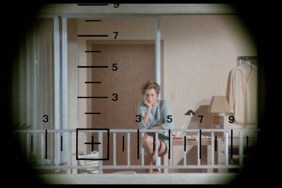

When Franck Khalfoun set out to remake William Lustigs notorious 1980 slasher Maniac (alongside his producer Alexandre Aja, director of High Tension and The Hills Have Eyes remake), the film moves from a pre-Giuliani New York City to the wilds of Los Angeles, a city bursting with hopeful stars and desolate stretches of land. The conceit of the film centers on the camera settling into the titular Maniac Franks (Elijah Wood) POV for the majority of the film. Maniac 2012 relies not only on the POV gimmick but also the practical effects which create the same squeamishness in the audience that the original did. Mixed with a pulsing synth-heavy score and ’80s nods (see: “Goodbye Horses” dance sequence, costuming and the films poster), Maniac offers a modern throwback, embracing the slick glossiness of the ’80s while also delving further into the diseased mind of Frank. While other modern remakes have attempted to humanize popular villains, Maniac 2012 makes it entirely clear that Franks fractured mind is beyond reproach and nothing will save him.

Almost Human (2013)

Joe Begos first feature film, Almost Human, is set in a rural American town under attack from extra-terrestrials who are abducting locals. The film opens informing the audience of the late ’80s setting using the same font as director John Carpenter favored for his films and uses the same ingenuity as Carpenter when creating the claustrophobic set of The Thing (1982) and filling it with some of the most revolutionary practical effects of its time. While Almost Human carries many markers of the auteur Begos pays homage to, its most telling influence is in the way the small rural town is shot evoking the way Carpenters camera panned over Haddonfield in the original Halloween.

It Follows (2014)

While David Robert Mitchells It Follows is set in an unspecified time with several technological elements added to confuse the viewer in regards to what the time period actually is, It Follows is a keen follower of John Carpenters lineage including the synth-heavy score. The film shares a relentless interest in its rural setting and creates a teasing relationship with the audience by having the titular “It” slowly emerge and trudge towards its intended victim much like Michael Myers. Carpenters Halloween is known for popularizing most of the all-important slasher tropes, especially that of The Final Girl, the female character who survives to the end by being (mostly) chaste and subdues the killer or force thats plaguing her. In Mitchells film, Jay (Maika Monroe) begins the films by having sex, a major no-no in the horror world, which in turn means that she will be slowly stalked for the rest of her life. Jays agency and sexuality are what brings the horror to her but her ingenuity means that she will fight to survive creating an evolution of the cliche.

The Guest (2014)

Adam Wingards The Guest offers a stylish cross between a machine-like genetically modified killer of the 1980s action films and the Final Girl trope, a blend which as Wingard has stated in interviews, came from Jason Zinomans book “Shock Value” about the emergence of genre films in the 1970s and ’80s. Wingard and his screenwriter Simon Barrett then imbued the film with the ’90s trend of the killer integrating into the family (Single White Female, The Hand that Rocks the Cradle). The film begins with the Petersen family mourning the loss of their son while in armed combat. His charming army buddy David (Dan Stevens) arrives on their doorstep one day solving all of their problems, but through a series of seemingly accidental deaths. This ’80s/’90s mashup storyline is filled with the same interest in intimate and rural settings as well as adding costuming pieces (the diner uniforms in particular) to add a specific yet timeless essence to the film. The Guest is filled with references from several decades creating a palette for the film that is both familiar and unfamiliar keeping the audience on its toes.