1995, a weird year for American cinema. There was a new Bond in Pierce Brosnan. Some young punk commercial director named David Fincher reinvented the serial killer picture. Michael Mann delivered what many consider to be his great masterwork. Adam Sandler starred in his first film. Paul WS Anderson turned the worlds goriest video game into megaplex trash art. Mel Gibson wore a kilt. Keyser Soze was behind the crime of the century. Jessie Spano took off her top (a lot). Nic Cage drank (even more). Clint cried. Anthony Hopkins somehow played Nixon. Oh, and two John Carpenter movies were released within a matter of months.

The first Carpenter title of 1995 was one of the best the director ever hung his name above. In the Mouth of Madness was the final picture in Carpenters Apocalypse Trilogy (a trio which also includes The Thing and Prince of Darkness), and capped the directors fascination with the end of all things quite well. The story of John Trent (Sam Neill), an insurance investigator hired to locate a Lovecraftian author (Jürgen Prochnow) after his mysterious disappearance, In the Mouth of Madness plays like Carpenters Greatest Hits record. Theres a fictional New England town, a cynical rogue at the center, questions about the nature of human existence, and (of course) anamorphic 2.35 photography accompanied by a punishing synth/guitar score. Its a movie that climaxes while Trent watches the world end over and over on a film loop, laughing his head off as he knows theres nothing left but utter psychosis.

In a way, this image feels like a culmination of Carpenters work up to this point, and acts as a divider between his silver screen Golden Era (Memoirs of and Invisible Man remaining an outlier, of course), and the abysmal Late Period most cinephiles discuss with disdain. His next in 95, Village of the Damned a remake of the 1960 Wolf Rilla film of the same name contains many of the distinct calling cards fans came to know and love over two decades of enjoying the directors output. But the movie also carries an air of flat dispassion, a feeling of indifference that is distinct and unsettling. Were one to watch Village of the Damned within close proximity of In the Mouth of Madness today, theyd be hard pressed to fathom these films came from the same artist during the same calendar year.

You can tell a lot about a directors relationship to the work by examining their cameo within a particular picture, and in Village of the Damned Carpenter plays an anonymous man at a payphone. Keeping the theory in mind, compare this bit part to an early appearance the filmmaker makes in The Fog (which is tonally the remakes closest cousin). In his 1980 cult classic, Carpenter plays a broke church handyman that has to beg for his paycheck a fictional subsistence not too far removed from how the director was living in real life after Halloween became the most successful independent film of all time. Following the slashers success (which was completely unbeknownst to Carpenter while he was shooting his Elvis Presley TV biopic), the director made a two picture deal with AVCO-Embassy and shot The Fog for $1 million. That was a huge budget hike compared to his $300,000 allotment for Halloween, but the director still wasnt rolling in financial reward. As the (in)famous story goes, Carpenter had to be talked into writing and executive producing Halloween II by his agent as a means to share revenue on the end product, resulting in the auteur pounding out the sequels screenplay over multiple six-packs of Budweiser.

Like The Fog (which was partially inspired by the 1958 film, The Trollenberg Terror), Village of the Damned is directly influenced by British horror. Only instead of drawing from the past in order to create another of his personal, old-fashioned picture shows, Carpenter decided to remake the original movie wholesale. Where The Thing saw the director utterly reworking Howard Hawks and Christian Nybys The Thing From Another World (one could even say the movie is more a direct adaptation of John Campbells short story Who Goes There?), Village follows the general plot of Rillas film rather meticulously. In fact, the movie is so close in overall storyline that David Himmelsteins 1995 screenplay is credited as being based on the 1960 script that was co-written by Stirling Silliphant and Ronald Kinnoch (the latter going under a George Barclay pseudonym). From even a basic screenplay level, theres a sense of general recycling that would sadly become prevalent in the directors work from here on out.

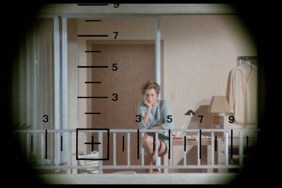

Obviously, Carpenters movies mostly live and die based on the directors singular visual style, and Village of the Damned still sports his usual widescreen fingerprint. The tracking shots are fluid. Opening with a POV soaring over the Pacific, a menacing force glides toward the coastal town of Midwich, its sole intention to impregnate the towns women with alien children. The golden hour photography is also striking, offering up a sun soaked antithesis to Antonio Bay. Like his best work, Carpenter knew his way around the iconography of his homeland, and that even the most manicured yard can feel malevolent if framed properly.

Readily apparent is the directors trademark cynicism. Where Rillas original captured an air of Cold War paranoia (the parents of Midwich fear that their children have been brainwashed), Carpenter embraces a government agent who is working under the townspeoples noses the whole time. Much how Abel Ferrara updated Invasion of the Body Snatchers to address his usual distrust of authoritarian bodies, Carpenter is using the classic sci-fi/horror cinema of his youth to channel his personal feelings regarding government. Yet outside of a few contemporaneousness updatesthe government offers to pay for the abortion of any impregnated woman who does not want to carry her mystery child to term (implying the powers-that-be will sacrifice lives in order to harness a new weapon)even instances of Carpenters world-weariness are fleeting and forgettable.

It doesnt help that Carpenter is barely able to get passable performances out of a rather weirdly eclectic cast of white folks. Kirstie Alley smokes cigarettes and plots behind closed doors, all while Christopher Reeve (in the last role before his tragic, paralyzing accident) plays noble doctor to an entire community of women on the brink of their collective water breaking. Michael Parés mumbling, meat-headed goofiness is thankfully brief, as he is the first to be claimed by the alien presences arrival (spoiler alert, I suppose). Possibly the most out of place is Mark Hamill, playing Midwichs priest, warning that the children born during the towns mysterious, otherworldly blackout are to be feared like the devil their hive mind working to destroy their elders. Thankfully, Carpenter backs all of the performances with one of his trademark scores (complete with twinkling synths) and punctuates the dullness with otherwise superfluous gore (an early moment where a man is cooked on his own grill is particularly gratuitous). Its as if the director realized while watching the dailies that his whole film seemed fueled by Quaaludes, and did anything he could to save it in post.

An argument could be presented that, with Village of the Damned, Carpenter made the movie he always wanted to make: a Hawksian tribute to the matinee B-Films he remembers watching as a boy. Though it would actually clash with the movies modernity, if the film stock had been switched from Super 35 color to black and white, Carpenter wouldve 100% achieved the old fashioned look hed venerated for the entirety of his career. Nevertheless, this is the problem with not only Village of the Damned, but the rest of Carpenters Late Period output as well. All of he pictures that came from April 1995 on feel like they run completely on nostalgia, both for a past he grew up with and helped create. Vampires (which may be the directors final wholly enjoyable picture) revisits the action/horror roots of They Live with limited returns. Ghosts of Mars attempts to recreate the siege picture formula Carpenter had already perfected twenty-five years earlier with Assault on Precinct 13. Escape From LA is a haphazard revisiting of Snake Plissken, capped with the worst onscreen moment of surfing ever committed to celluloid. Its sad to watch a master run completely out of gas, but maybe thats why he retired to a private life of chain-smoking, video games and Lakers games following The Ward there were just no more stories John Carpenter wanted to tell.

—

Jacob Knight is an Austin, Texas based film writer who moonlights as a clerk at Vulcan Video, one of the last great independent video stores in the US. You can find find him on Twitter @JacobQKnight.