A significant Black or African American presence in horror films is neither easy to unpack nor discover. Since Im putting emphasis on the word significant, it is crucial to look beyond the forgettable body count and hyperbolic comedic relief caricatures in the entire genres history. Once we do, we can begin to at least wonder if this significance exists.

Duane Jones Ben in Night of the Living Dead (1968) is amongst the prime examples of groundbreaking and significant depictions of Black characters and race relations in the genre, especially for its debut during the height of one of the most racially charged times in American history. But his presence operates much more on symbolism and micro-aggressions. How Ben interacts with white characters is practically carbon copy of interracial turbulence: Barbaras comatose-like fear of his presence, or Harrys antagonistic approach and insistence on challenging Bens authoritative position. Popularly known amongst horror fans, writer/director George Romero picked Jones for the role with no foresight of radical inclusivity. Its legacy and commentary on race was purely coincidental.

Characters who are Black in films often offer some nuanced insight into how we deal with matters of race. In horror, interpretations can be unsettling because of the clear dichotomy between good and evil and the more obscure fears we harbor about the unknown. Conjuring discourse on the stock Black character in a horror film with no moment where their skin color is considered has been a fun project, but why dont more horror films directly deal with race? What does it look like when a horror film takes on the horrors of racism and race relations?

I follow a question with a question to not only explore the ways in which the horror film has been used as a tool to investigate fear based on racial difference, but also African American agency and complexity in character, exposing the nightmares of this racialized group of individuals. Blacks in horror have somewhat of an unsung history. This month, I wanted to further the narrative that African Americans have a distinct place in horror films in front and behind the camera, as well as continue to have a desire to show how race effects all of our lives.

Dr. Robin Means Coleman, author of Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present examines what Black representation in horror reveals about Black culture, identity, and our discussions surrounding what horror tells us about race. Two categories are at the crux of how we make distinctions between how American discourses and politics about race have been interpreted and depicted throughout the history of the genre: Blacks in Horror Films vs. Black Horror Films.

Blacks in Horror Films make suggestions about where an audience places the horrifying, usually within the racial Other (Candyman). Black Horror Films depict horrifying social inequalities and personas as monstrous, with Black, centralized protagonists unmasking racist tropes and exercising empowerment (Blacula). Im briefly using the examples Candyman (1992) and Blacula (1972) as theyre widely known, and arguably horror classics.

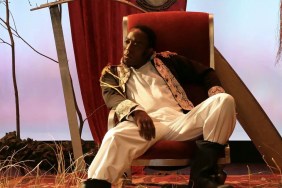

Whats fascinating is that throughout horror film history, the Black monster is prevalent in both categories. The monster is offered a context that gives him a history; humanizing his existence is critical in depicting a tale rooted in the problems of racism. Blaxploitation classic Blacula, a Black Horror Film begins in the year 1780 with an African Prince, Mamuwalde (William Marshall) and his wife Luva (Vonetta McGee) seeking to negotiate with Count Dracula to curb the slave trade. Unmoved by his unprofitable request, the situation soon escalates into violence as the Count bites and turns Mamuwalde into Blacula. As a prince, Mamuwalde used his position of power to confront his white male counterpart in ending the systemic oppression of scores of enslaved African people. Count Draculas move of (white) superiority came when he turns Mamuwalde into an immortal bloodsucker, as well as renaming him, akin to a Master/Slave dynamic. This prologue of historical fiction enriches the story that follows Blacula when he is exhumed in early 1970s Los Angeles. The audience begins the tale with the tragic knowledge of how Blacula came to be, forced into this monstrous being in an act of power and suppression.

The Blacks in Horror film Candyman offers us the story of Daniel Robatille, an inheritor of wealth and a sophisticated Black man commissioned to paint the portrait of a White Illinois landowners daughter around 1890 (this is fleshed out in sequel Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh). When the two fall in love, and she becomes pregnant, an angry lynch mob catches Robatille; sawing off his hand, smearing him with honey, leave bees stinging him to death, and scatter his ashes over what are now infamously known as the site of the Cabrini-Green projects in Chicago. As a sympathetic yet ruthless spirit-turned-urban legend, Candyman is a figure of fear essentially created by the racialized fear of miscegenation.

Though Blacula and Candyman fall under distinctive categories according to Coleman, both successfully force us to directly look at the historical impact race has and uses horror to show its monstrous effects. We cannot position Blacula nor Candyman as one-note antagonists. They are markers for understanding how racial injustice operates and complicates a viewers concept of evil within the confines of each film.

Currently, there are Black filmmakers who look to this tradition and make an even more direct attempt at demonstrating the way in which race operates in horror films. Octavia: Elegy for a Vampire promises to be a character-driven portrait of a highly conscious vampire that, after 150 years as a witness and victim based on her intersectional experience as someone who is both Black and a woman, reconsiders what it means to have immortal life. Director and screenwriter Dennis Leroy Kangalee has outlined in lengthy statements the intent of his film are rooted in the effects of colonization.

Actor and comedian Jordan Peele is working on co-writing and directing a straight-no-hybrid horror film with Darko Entertainment that, in his words, deals with the fears of being a black man today. The fears of being any person who feels like theyre a stranger in any environment that is foreign to them. It deals with a protagonist that I dont see in horror movies. Most known for comedy, it was a nice surprise to discover that his ultimate goal has been to write and direct horror films.

What Lee, Peele, and a healthy handful of independent Black filmmakers represent are valiant attempts at centralizing and humanizing the fear within and outside of Black characters, with care to the horror genre. It seems small, but accurate, to use the word hopeful, considering what horrors past has demonstrated and how many Black artists its inspired to build their own unique stories. Horror has a well-rounded, albeit comparably small Black history. That doesnt deter from its amazing strides in telling tales that make us think about race in meaningful ways. If Ben, Blacula, and Candyman retain such a stark impact on horror fans, the genre can continue to live up to its transgressive title.

—

Ashlee Blackwell is the founder and managing editor of Graveyard Shift Sisters, an engaging celebration of Black women in the horror and science fiction genres. She currently resides in Philadelphia.