Looking back on Freddie Francis’ underrated 1973 horror anthology Tales that Witness Madness

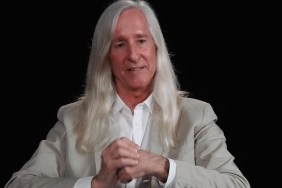

Often mistaken for one of Amicus Pictures’ horror anthologies, Oscar winning cinematographer and veteran genre director Freddie Francis’ 1973 omnibus Tales That Witness Madness is a superior British horror film and one of the finest examples of the multi-story shocker. Amicus of course cornered the market on these sorts of films throughout the 1960s and ‘70s and while they were all entertaining and skillfully produced, only 1972’s EC comics riff Tales from the Crypt truly felt like it was pushing boundaries, like it was dangerous in some way. And despite that film’s domestic PG rating, it still stands as one of the scariest horror movies this writer has ever seen. And it was directed by Francis. And Tales that Witness Madness is directed by Francis. You see where I’m going with this…

Tales – whose title oddly foreshadows Charles Bukowski’s celebrated short story collection Tales of Ordinary Madness – opens with a dynamic credits sequences with green X-rays of human skulls and brains dissolving across the screen, a clear indication that this picture is concerned with the cornerstone of the greatest genre pictures, that of the shadowy, mysterious and easily damaged corners of the human mind. Its set up echoes that of Amicus’ Asylum (directed by Francis’ fellow Hammer Horror colleague Roy Ward Baker) but Francis – again, a trained DP – frames the film with weird angles and low camera set ups, making us feel like something is dreadfully wrong right from the start.

A doctor (Jack Hawkins, in what was his final film) visits an impossibly antiseptic, retro-futuristic insane asylum run by the kindly Dr. Tremayne, played by future Halloween legend Donald Pleasence, already at this point a stalwart of the European horror boom. Like in Asylum, Tremayne leads his visitor to four separate cells, where near-catatonic patients while away their days staring at walls. Each patient’s troubled past serves as a segment of the picture.

The first tale “Mr. Tiger”, is the scariest, a graphic quote on the classic Ray Bradbury story The Veldt. In it, a little boy named Paul (Russell Lewis) lives with his hideous parents in a lovely English manor. The couple fight endlessly. About everything. And Paul simply withdraws, focusing on his toy piano and his new “imaginary” friend Mr. Tiger, an invisible brute that has a hankering for raw meat and bones. When Paul begins stealing these foodstuffs from the fridge and when claw marks begin appearing on doors and walls, mom and dad find enough common ground to talk to their son only to discover that the lad’s imagination might be a bit more fertile than they thought. I remember watching this film as a child with my mother on cable and recall how frightened and disturbed I was by this story’s climax and, admittedly, although ludicrous now, it still makes for a shivery psychotronic wallop.

The next story, “Penny Farthing” is a semi-goofy romp with its roots in the Victorian ghost story. In it, the owner of a London antiques shop (Peter McEnery) becomes fixated on the ever-changing portrait of his late Uncle Albert and the massive, vintage bicycle left to him by his aunt in her will. When the man sits upon the penny farthing, he is inexplicably whisked back to the Victorian era where he meets and falls in love with a young woman named Beatrice who is the ringer for his girlfriend (both characters played by The Bird With the Crystal Plumage’s Suzy Kendall). Turns out the longer he spends in this phantasmagorical alternate dimension, the stronger the spirit of his long dead Uncle gets. Despite some of the silliness in this installment, Francis’ directorial skill and eye for macabre detail prevail.

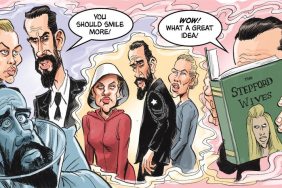

The most famous tale of the Tales comes next with “Mel”, a perverse romp that I wish could be extracted from the movie and fleshed out into a feature film. Francis’ Tales from the Crypt star, sexpot Joan Collins plays Bella, whose husband (Michael Jayston) brings home a desiccated tree trunk and proclaims it to be an art piece. The name “mel” is carved into the tree and that’s exactly what he calls it, becoming more and more connected and enamored by the thing. Soon Bella is genuinely threatened, the cuckold wife of a man who has taken a tree as his lover. She forces her deranged husband to make a choice. He does. You can probably guess the outcome. Needless to say, it ends rather happily…if you’re a champion of man/bark love, that is.

The last story, “Luau”, is the weakest but still quality Grand Guignol and its essence likely served as the inspiration to the misleading and corny theatrical poster that was used to sell the movie and ensuing video release. Vertigo’s still gorgeous Kim Novak plays a book agent in love with her new client, a Hawaiian writer named Kimo (Michael Petrovich). But the writer seems far more interested in her comely daughter. When Kimo sets up a lavish celebratory Luau feast for mother and daughter, his designs on the younger woman become carnivorously clear…

Like in the oft mentioned Asylum, the framing narrative with the two doctors serves as the fifth story, with Nicholas believing Tremayne – who believes all these wild stories to be fact – to be himself insane. But is he? We won’t spoil the stinger of an ending except to say that our pal “Mr. Tiger” makes a welcome re-appearance.

Tales that Witness Madness is a strong, potent horror film and its R rating is deserved. Although there isn’t any graphic sex, the film is cruel, violent and often alarmingly gory and even though I did watch it as kid…it’s really not a good one for the tots. My own mother denies ever showing it to me. Funny how that works. Fascinatingly, it was one of two films written by veteran British actress Jennifer Jayne (from Amicus’ Dr. Terrors House of Horrors), the other being 1974’s bizarre Son of Dracula, both written under her pen name Jay Fairbank. It’s a shame she didn’t write more as the script for Tales is literate and pulpy in equal measures and the dialogue believable throughout. And the score by Bernard Ebbinghouse is a blend of symphonic Gothic horror and lapses into a contemporary rock sound in key moments. Again, it serves the kinky, loose nature of the movie perfectly.

And while modern horror anthologies serve as short film showcases, with different directors and styles and points of view bashed against each other, Tales – and its ilk – benefits from the consistency of a vision that a single director brings to a project. It feels wholly satisfying and is truly one of the weirdest and most undervalued portmanteau shockers ever made.

If you haven’t seen it…do so.